by Nick Plasencia

Colleges that have investments in the lodging space can take steps to mitigate COVID-19-related cash flow challenges, explore temporary alternative uses and position the investments for future growth.

Nick Plasencia wrote this article for University Business published on June 18, 2020. The full article is available on the University Business website.

_____________

On- or near-campus hotels, particularly those owned by colleges and universities, have experienced largely uninterrupted success over the last several years. While the COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted normally bustling campuses, the impact for university hotels has been particularly troublesome. Fortunately for schools that do have investments in the lodging space, there are a number of steps that may be taken to mitigate current cash flow challenges, explore temporary alternative uses, and position the investments for future growth.

College hotels have historically enjoyed stable growth

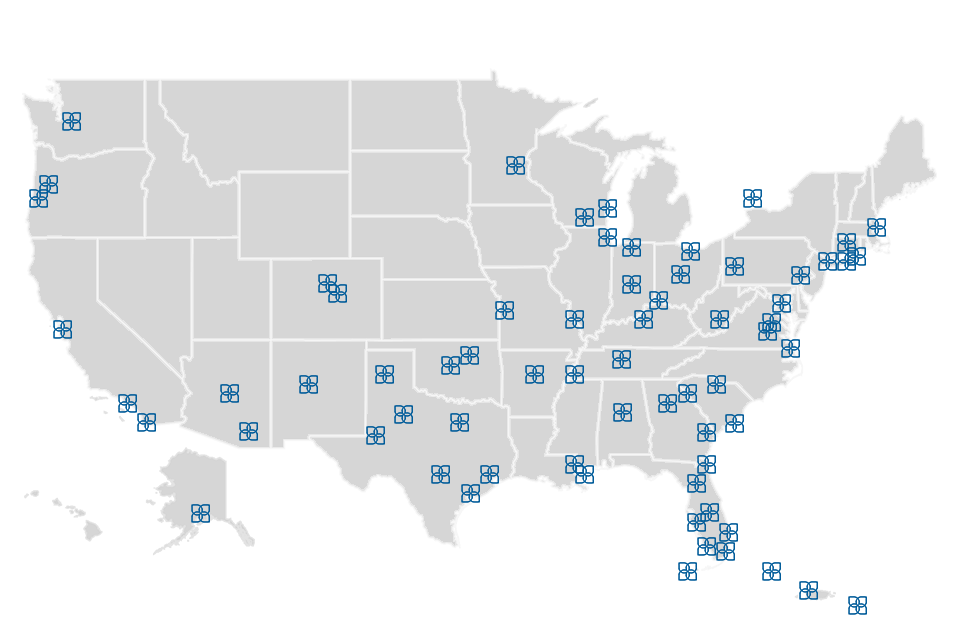

Over the course of this economic cycle, university communities have been fertile grounds for successful hotel operations, driving a spate of development and investment activity. Driven by rising enrollments, physical expansion and development, and an inflow of public investment from state and federal governments, college towns across the country have experienced economic growth that many larger, gateway cities have struggled to find. Consistent lodging demand on university campuses is typically spurred by year-round activities including move-in and move-out weekends, athletic competitions, graduations, hospital-related overnight stays, prospective or new employees, frequent conferences and meetings, and corporate visits from university partners and vendors.

Many universities have harnessed this captive demand by acquiring on- or near-campus hotels, developing new lodging facilities, or re-investing in their existing properties.

A host of schools have also structured arrangements with unaffiliated third-party hotel owners, developers and managers to lease university-owned land parcels with hotels or hotel development sites atop them. These long-term ground leases create lucrative payment streams for the universities or their foundations, typically in the form of base rent plus a percentage of the hotel revenues. In addition to the financial benefits of owning a hotel, universities utilize their lodging establishments to foster a welcoming environment for campus for visitors, recruits and alumni, employing ubiquitous branding to promote the school’s culture.

Covid-19 disrupts campus life and hotel demand

The onslaught of business interruptions brought on by the Covid-19 pandemic has turned once surefire demand for university hotel rooms on its head. Indeed, nearly every facet of the global lodging industry has been battered; domestically, occupancy rates have been depressed since late March, and Revenue per Available Room (“RevPAR”), the hotel industry’s key performance metric, was off by a historic 83.6% by the second week of April.

In the wake of the virus, athletic events, parent visits, conferences and university-related corporate and government travel—not to mention on-campus classes—have come to a screeching halt. Officials at many colleges are still pondering what the fall semester will hold, including whether they will be able to offer a traditional on-campus experience in the coming academic year at all.

With far fewer guests to fill their suites, restaurants, bars and ballrooms, many hotel owners across the industry have opted to temporarily suspend hotel operations. Those that have remained open have resorted to furloughing most property employees, oftentimes running a hotel with a skeleton crew of five to 10 individuals.

Despite the cost savings of reducing personnel and closing pools, ballrooms, restaurants and even entire wings or floors of hotels, a shuttered or scaled-down hotel operation still results in sizable cost deficits. In addition to residual staffing costs, overhead such as electric utilities to keep emergency systems and climate control running, insurance costs, property taxes, brand-affiliated fees and expenses paid to the hotel management companies ring up a daunting bill. For a large city-center hotel with a restaurant and meeting space, this monthly operating loss can run well into the six figures.

Bridging the gap

On eerily quiet campuses today, many universities are grappling with negative cash flow at their owned hotels and with ground lessees who are unable to pay rent. Fortunately for university stakeholders, there are levers to pull to mitigate expenses even further while positioning hotels to thrive when demand inevitably returns.

The first step is expense triage. While many expense reduction tactics are obvious, there are dozens of ways to reduce cash burn even further, including:

- restructuring contracts with brands and management companies to reduce fees

- negotiating mortgage forbearance with lenders

- accessing furniture, fixtures and equipment (FF&E) reserves typically set aside for capital improvements

- pursuing relief from insurance agencies and tax bodies as appropriate.

Employing tactics as seemingly minor as reducing lawn sprinkler usage, optimizing thermostat settings, disabling unused elevators, reducing filtration on closed pools and unplugging unused refrigerators can amount to considerable savings.

Next, hotel owners should prepare for returning demand. By examining data from parts of Asia and Europe that have been successful in reopening their economies, it is evident that lodging demand is ticking upward, albeit slowly. Hotel owners should assess their property management teams’ 2020 and 2021 budgets and perform breakeven analyses to determine the ideal time to begin ramping up property staffing, sales and marketing, and inventory purchases. Owners should enact new, certified cleanliness standards, evaluate introducing novel concepts into their restaurants and outlets, study the competitive hotel inventory, benchmark performance against comparable properties and also against prior economic recoveries, and scrutinize planned capital expenditures.

While short-stay transient demand is likely to return most quickly, group demand emanating from conferences and meetings is likely to greatly lag, potentially until a vaccine is widespread. Hotel management companies today should be prioritizing replacing those blocks of group rooms with other sources of revenues, perhaps through longer-term contracts with airlines or government agencies.

Furthermore, university hoteliers can benefit from the campus ecosystem in unique ways related to hospitality.

Underutilized ballrooms and restaurants may have alternative uses as study halls, fitness facilities, student lounges, and snack bars. Administrators should evaluate formalizing relationships with campus health systems to augment guestroom demand at university-owned hotels. Universities may also be more influential in directing university-related business to their owned hotels, although relationships with other campus partner hotels must be taken into consideration.

Institutional officials may also need to consider utilizing hotel rooms for COVID-19-related displacement. Some schools are evaluating the prospect of single-occupancy student housing for the fall semester. Owned hotels could be used for overflow capacity, and long-term contracts can also be struck with campus hotel partners who would welcome the steady business, even at discounted rates. Alternatively, many universities are examining saving some of their student housing stock for quarantine situations, should they arise. Hotel room inventory on campus can provide additional flexibility to these schools.

While the pandemic has created unprecedented disruptions on college campuses across the country, and especially within university-owned hotels, administrators have the opportunity to be proactive in leveraging their hotel real estate in new ways while preparing for growth when traditional demand inevitably returns.